Securing Transactions In A Trust-less World.

Why do we trust each other?

Quick Note: I will be using the tokens created in this web-app to describe some of the ideas you will be digesting in here. Feel free to check it out while reading this.

In the world we live in, we regularly make transactions to meet our day-to-day needs. Whether it being in the market, or online or at work, interacting with other people to acquire what we consider necessities is a standard in life, a regularity in which for most, began as soon as we could communicate. Theres a lot that goes on when you make a transaction with someone, because it’s effectively just a regular interaction with some monetary or valued context. Think of body language, facial expressions, accents, all meant to create some sort of informal trust while engaging with a potential client or employer. In the context of communication, they are used to effectively pass a message receptively, but in the context of a transaction, they are meant to create trust.

When it comes to trust, up until today we’ve operated under the mechanics of blind trust, or informal trust. For instance, when you sign up for an account on an exchange, you typically submit personal information such as your email and name, and when it comes to some, something more personally identifiable such as your passport or national identifier. Notice how in this example scenario, I have to commit to using their service with the implied hope that they will act trustworthy with my information and everything I choose to invest into the site; in the case for most exchanges, its handling all my money and coins. Of course reputation goes a long way pre-establishing trust, but the same cant be said for normal everyday interactions.

Consider this, I wish to acquire some human resources for undertaking a construction job somewhere. The transaction in this case would involve withholding the agreed upon payment until the work is done, and in its place being a promise in exchange for the service since trust does not exist between me and my hired hands. It’s been the case for most of history, and if you think about it, has been the root cause for a lot of employer employee conflicts, at least prior to the advent of most legal systems that exist today. And so far it’s worked fine, but the case cannot be said for transactions that occur online; in a space that supersedes most jurisdictions and social spaces, a problem that is substantially amplified by the advent of cryptocurrencies.

We’ve all heard the cryptocurrency narratives; internet money, peer to peer trust and trust-less transactions. That last message though is a bit misleading, because what they really mean when they say ‘trust-less transactions’ is more, trust-less consensus; this idea that instead of relying on one institution that we trust to keep track of who owns how much, we rely on each other as peers all knowing what each owns, and this decentralized consensus mechanism to actively modify and add to the blockchain ledger perpetually. Trust-less transactions has never been hacked before, because if it was, there would be world peace. Most conflicts that have happened throughout history stem from broken trust and unfulfilled transactions; but there could be a new way of securing our transactions, and it comes from one of the oldest ideas of blockchain, that being staking.

Staking as a concept isn’t new. It’s how most blockchains today secure themselves and their consensus mechanisms. Basically, instead of burning energy and computing equipment solving problems to create trust with the network and acquire the right to write the next block, you create trust by submitting something of value that you can lay claim to after your service is complete. Essentially, I trust you because I control some of your money, and if you break my trust, I have the right to deny you access to repossess some, if not all of your money back after your service is complete. It’s a really neat solution, because essentially the problem of trust is solved by simple value exchange instead of energy expulsion. The ledger itself acts as an escrow and consensus authority in the transaction, instead of a traditional bank or centralized authority.

This idea can be hijacked to not just secure transactions involving validators and the network, but also everyday transactions with real world connotations involving two peers, with the network and a well structured contract being the arbitrator. This is where the idea of smart contracts come in; they are special programs deployed on a blockchain such as ethereum that help execute custom instructions on a decentralized network. Think of them as apps on your phone, except the app is a smart contract and your phone is a blockchain. With this ability to construct custom logic that helps arbitrate a transactional interaction between two parties, the idea of trust-less transactions can be achieved. This can only work if the two or more parties involved agree to some form of consensus structure to be followed while dealing with the value being exchanged, to ensure that absolute trust is created and the security of a given transaction is maximized.

Have you ever heard of unanimous consensus? It’s one of the strangest forms of consensus that is often labelled as unusable; but for most of our peer to peer transactions, it’s usually whats used. Unanimous consensus is a system of consensus in which all parties have to agree to an intent for it to be valid, otherwise it’s invalid. I like to refer to it as the root consensus mechanism because all others are built on this one idea; we all agree on this one network that, at least 80% of the miners involved have to vote yes for a source code update to be accepted in the network; we all agree as a society while voting that at least 51% of the cast vote should be received by a winning candidate for them to declare victory; We all agree… we all agree… we all agree. While yes, it is true that this when applied directly doesn’t scale well, on a small scale however, between two people for instance, it is perfect because all parties involved would not knowingly share partial control of their money if they did not intend to fulfill their end of a given transaction.

I hope you see where I’m going with this; a smart contract that allows for the creation of custom accounts whose funds are controlled by two or more participants through unanimous consensus, made specifically for the purpose of arbitrating a given real world transaction. The custom accounts, or contracts, would feature an array of different settings and configurations made for specific scenarios and use cases, all to ensure that trust is established and maintained for a select period of time, preset by the participants of the contract. This is exactly what has been done for the contracts section of E5; a section specifically for the creation and facilitation of such custom accounts made for creating trust for securing real world transactions and transaction-like interactions.

I think its best if this idea is clarified further with an illustration; a simple peer to peer swap. Alice has 1 bitcoin and wishes to swap it for 20 ethers with Bob. In most peer to peer platforms, Alice being the initiator would have to send Bob the full bitcoin after establishing the transaction’s context with him, and hope that Bob would fulfill his end of the bargain by sending her the agreed upon 20 ethers thereafter. Notice how trust isn’t created inherently, but through other means such as ratings, transaction history on the platform and an overseer who would hold power to revoke their access to the platform upon failure. This would extend to stuff like personal, private and identifiable information that could be leveraged against Bob upon malpractice. Let’s compare this with using contracts.

Bob in this case would have a contract since he’s the recipient of the transaction request, and the contract would have his existing staked tokens, in our case SPEND. Alice would enter the contract by submitting an entry fee, usually the amount required for creating trust in the contract, in SPEND. So Bob and Alice would be part of the same contract and both would have staked money in the contract they wish to repossess after the transaction is complete. Since trust is established, any of the two parties can be the first to initiate the transaction; Bob can release the 20 ethers first or Alice could send him the bitcoin first. An important thing to note here is that, the amount of staked tokens dictates the amount of trust created, and is a relationship that directly proportional; The more money we stake, the more trust we create. So for high value transactions such as the one described in the example above, a relatively high amount of SPEND would be required to be staked to create sufficient trust to facilitate the transaction.

This idea can be taken further; instead of just securing transactions, contracts can also be used to pre-pay services entirely. For instance, if I were to hire a contractor to do a job for me, I could enter his contract with the agreed upon amount and keep it in his contract to assure him I intend to fulfill my end of the deal. Then once the transaction is complete, I can just forfeit control and exit the contract. When unanimous consensus is employed, almost anything goes, any nature of transaction can be created, secured and fulfilled, so long as the value of the underlying asset is maintained. This is where END comes in by the way; if you cannot ascertain that the mode of value transfer, that being SPEND, will maintain its value for the period of the transaction, then END can be employed for use since its value is pegged to the value of the ether used to acquire it, an asset whose value will be perpetually existent as long as the network itself remains uninterrupted.

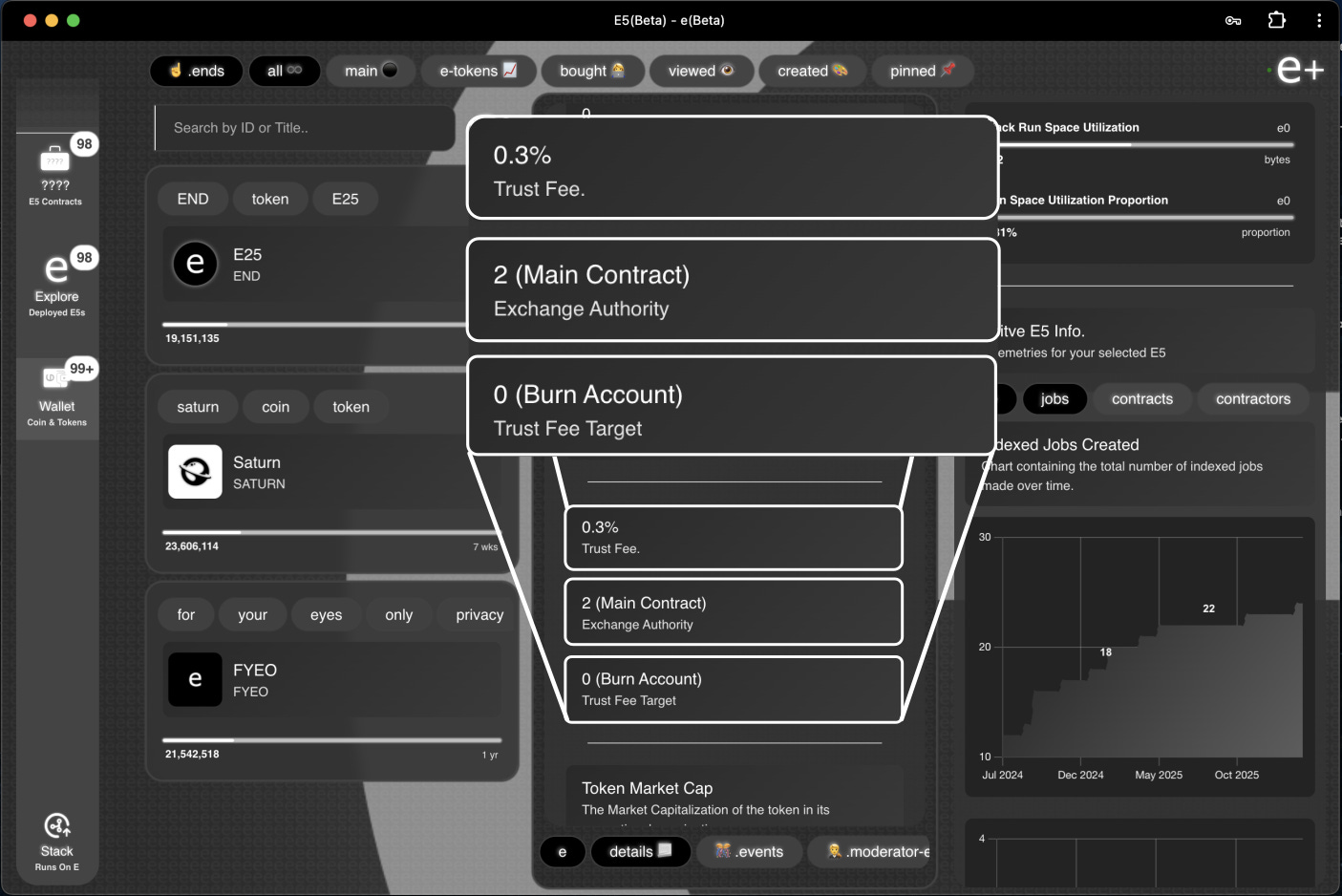

In my previous post, I mentioned that END is a token whose supply is perpetually reduced through burning, with the intended purpose of inducing perpetual inflation (the steady rise in its price) against the underlying ether used to buy it. This is where that burning would be implemented. No fee is incurred while entering a given contract or while exiting a given contract, but a fee is incurred, called a trust fee, when attempting to withdraw funds from the contract. All tokens require a trust fee, a proportional value which is set by the author of the token; In the case for SPEND, its usually the main contract; a contract used to control the entire state of the deployed smart contracts and the main tokens; and in the case for END its the burn account (account zero).

A trust fee is basically a cut on all value used to create trust in a contract using a given token, with the token’s exchange authority being the account responsible for setting the proportion itself. When you create a token on E5, you are the tokens authority unless specified otherwise in the settings. Contracts can also act as authorities that control the configuration of a given token’s exchange through consensus, with special permissions such as to change the trust fee, freeze balances and reconfigure the token’s basic access features.

However, there might not always be a time when unanimous consensus is applicable. For instance, when controlling funds as a large group to fund various projects. In this case, setting a target that is not completely unanimous makes more sense. On E5, this is called majority consensus, and is used for controlling a sub-category of contracts called workgroup contracts. So by default, this consensus majority proportion value is set to 100%, meaning its unanimous consensus, or a target of 100% yes votes during arbitration. This value, the 100%, can be changed to whatever value is needed. For instance, if an organization wished to control funds moving out of the contract using a majority consensus, a value of 72% could be set; meaning consensus is achieved when 72% of the votes cast are positive.

This idea can also be paired with voter weights. In some consensus mechanisms, certain votes hold greater power than other votes. For instance, in a vote cast by the board of directors of a given organization, a board member with a higher stake would have a greater weight on their vote than another board member with a relatively lower stake. On E5, a given contract could be paired with a specific token exchange, and the weights of each voter could be tied to the amount of tokens they possess. So if Alice had twice the number of tokens in the voter weight exchange of a given contract when compared to Bob, her voting power would be double that of Bob; and would easily be able to sway a given vote in her favor, owing to the fact that she has a greater stake in the contract.

I encourage you to take a look at one of the contracts in the contract section of E5 for more neat features like these that have been implemented.

If you’re into these sorts of ideas, feel free to check out my repository and its app deployed online.

e.